Interview by Patrick Folliard

Documenting Life Changes / February 6, 2004

Washington Blade

“All I write/ vanishes/ before/ it is written”

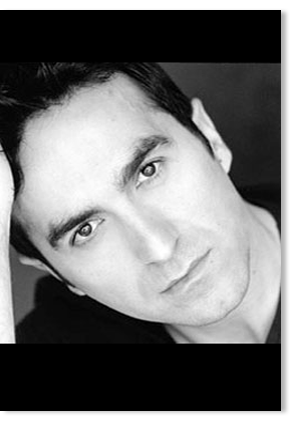

After writing this simple four-line poem, gay poet Mariano Zaro realized he had opened a door that would lead to other rooms and spaces. He knew instinctively that the words belonged to a larger body, but he had no idea what shape this body would eventually take.

As it turned out, five years later the poem, now titled “Poem #1”, has taken its place as the first of 30 entries in Zaro´s collection of bilingual poetry, “Poems of Erosion/Poemas de la erosion”.

“It wasn’t until I actually finished the book that I realized its them was the history of my disappearance,” he said from his home in Santa Monica, California. “I don’t mean this in a literal way, of course, there are many levels of disappearance. My first disappearance was the result of a cultural dislocation. I left Spain and moved to L.A. almost 10 years ago. At some point, I lost track of who I was and was unable to figure out my new identity,” he said. “It happens to a lot of people in the same situation, and it’s both scary and uncomfortable. In coming, I thought I was too strong for something like that to happen to me, but I was wrong.”

According to Zaro, 40, the second erosion of self was somehow connected to a loss of youth. At certain age, he believes, we either put to death the hope of the person that we dreamed to become, or the fantasy simply dies on its own. And when this takes place, and we settle on being whom we actually are, there is a time when we mourn for the idealized persona that we might have been. “And finally the third erosion is a more personal level,” Zaro said. “In order to make my relationship with my partner work, I hid instead of being present. I wasn’t engage and didn’t deal with any discomfort. Things appeared to be working and flawless, but nothing was really happening. There was no emotion behind the actions. I had disappeared from self.”

When he was writing the poems in the collection, Zaro said all these feeling of disappearance were very intertwined. “It is only now form a distance that I’m able to talk about it so scientifically and categorize my feelings,” he said. In this collection, the poet, who teaches elementary school in Los Angeles, features an English and Spanish version of each poem. “I have made a commitment to write my poems in both languages,” he said. “I have no choice: Life and crises happen to me in both languages, so I have to use both to write about it. Also, I have two tools of expression, and in using both, I’m able to pare down the words and make my writing less fussy.”

Zaro strives to write poetry that is honest, avoiding temptation to create anything “shiny or showy”. It’s important to him that a poem is clear enough for the reader to become engaged, but it also needs “a little space and silence” so the reader is able to finish and, ultimately, to create the poem himself.

Born in Borja, a small town in Spain, Zaro laughingly recalls a child of five dictating his first poems to his mother. He attended the university of Zaragoza where he earned a master´s degree in Spanish literature. During college, Zaro contributed to many literary magazines, most of which didn’t make it past the second edition. Like many of his literary idols, he was determined to live the glamorous life of an expatriate. He bypass Paris, Tangiers, and New York for Los Angeles, where by day teaches a mostly Latino third-grade class.

Since completing “Erosion,” Zaro is concentrating in prose. The first project is titled “Theme and Variations”. The second is a collection of portraits, detailing some of the eccentric women that Zaro encountered as a young boy in Spain, including a former model, and a very old lady who travels with a pet monkey.